Introduction

Can you learn to appreciate aromas such as spice, petrol, and even gamey or foxy notes in wine? And would you want to, or should you? How can you better understand the taste of umami in what you eat and drink? How do culture and lifestyle influence your perception of the aromas and taste of wine?

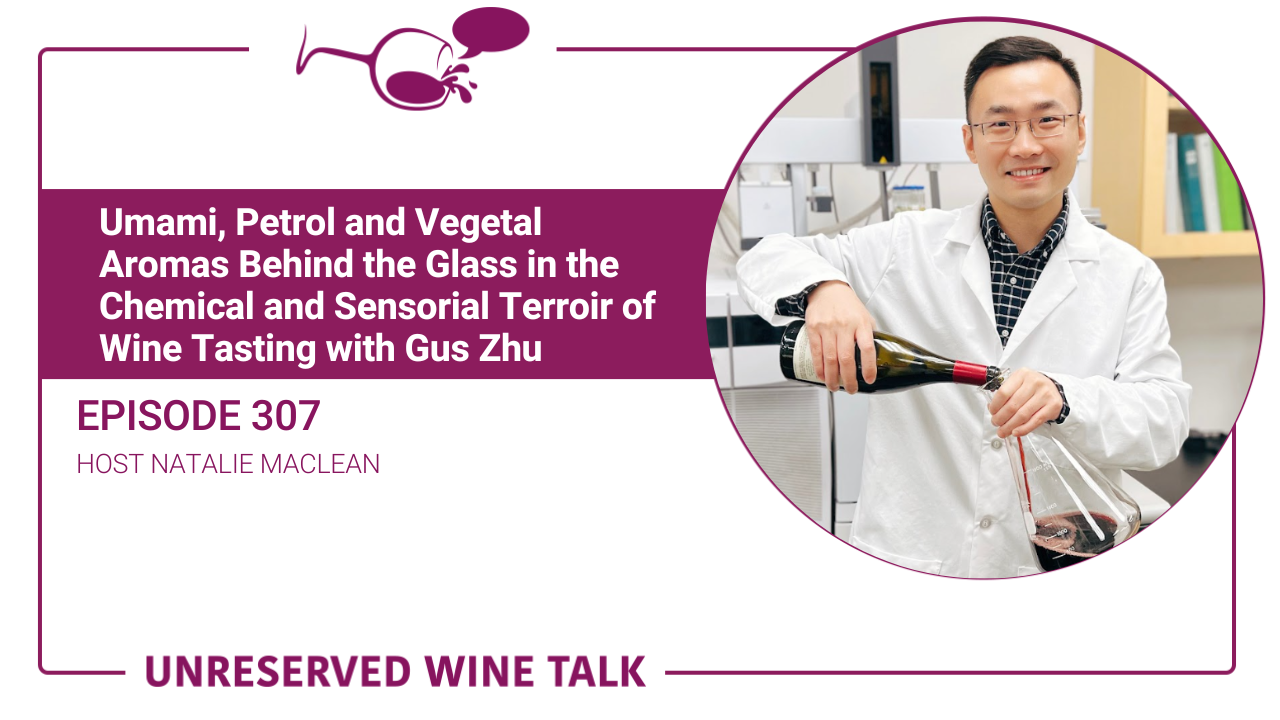

In this episode of the Unreserved Wine Talk podcast, I’m chatting with Master of Wine, Gus Zhu.

You can find the wines we discussed here.

Giveaway

Two of you will win a copy of his terrific new book, Behind the Glass: The Chemical and Sensorial Terroir of Wine Tasting.

How to Win

To qualify, all you have to do is email me at [email protected] and let me know that you’ve posted a review of the podcast.

It takes less than 30 seconds: On your phone, scroll to the bottom here, where the reviews are, and click on “Tap to Rate.”

After that, scroll down a tiny bit more and click on “Write a Review.” That’s it!

I’ll choose two people randomly from those who contact me.

Good luck!

Join me on Instagram, Facebook and YouTube Live Video

Join the live-stream video of this conversation on Wednesday at 7 pm eastern on Instagram Live Video, Facebook Live Video or YouTube Live Video.

I’ll be jumping into the comments as we watch it together so that I can answer your questions in real-time.

I want to hear from you! What’s your opinion of what we’re discussing? What takeaways or tips do you love most from this chat? What questions do you have that we didn’t answer?

Want to know when we go live?

Add this to your calendar:

Highlights

- What was the moment Gus realized he wanted to make wine his career?

- How did it feel to become the first Chinese Master of Wine (MW)?

- Which aspects of Gus’ multicultural education helped him pass his MW exam on the first try?

- What is Gus’ book, Behind the Glass, about?

- What makes Behind the Glass different from other books on wine science?

- What are chemical terroir and sensorial terroir?

- What was the most surprising thing Gus learned while researching and writing Behind the Glass?

- Why is the concept of the “tongue map” wrong, and what do we now know about how our tastebuds work?

- How can you better understand the taste of umami?

- Can you learn to appreciate vegetal and herbal aromas in wine?

- How do terpenes present in wine aromas, and why do people like them?

- Why might supertasters be at a disadvantage in the modern world?

- How do culture and lifestyle influence your perception of the aromas and taste of wine?

Key Takeaways

- Can you learn to appreciate aromas such as spice, petrol, and even gamey or foxy notes in wine? And would you want to, or should you?

- As Gus explains, we evolved to reject certain smells for our survival. For example, if a plant or fruit or food smells vegetal, it’s a sign of under ripeness so it either doesn’t taste good or isn’t nutritious enough for consumption. In some cases, it could mean that it’s poisonous. So it makes sense then that we may not like vegetal aromas in wine.

- How can you better understand the taste of umami in what you eat and drink?

- In Asian countries, Gus says, they have a longer history with fermented food and drink. They also don’t over season or over cook protein dishes so that the taste of umami remains. Umami comes from the amino acids in protein, but we often get confused because we combine our proteins with fat, salt, and other things. If you barbecue a mushroom and don’t season it, the juice or broth released in the little dent in the mushroom is a savory, yummy, umami taste.

- How do culture and lifestyle influence your perception of the aromas and taste of wine?

- Gus believes that we should pay more attention to what we eat and drink. In China, they eat lots of different parts of animals but in North America, especially in the United States, he finds that people tend to eat meat that’s very bland. He believes that people who like the Chinese experience a more diverse range of flavours and develop a greater appreciation for them. Similarly, we develop a greater vocabulary to express what we’re eating and drinking when we think about it.

Start The Conversation: Click Below to Share These Wine Tips

About Gus Zhu

Gus Zhu is the first Chinese national to become a Master of Wine. He works as a research and development scientist at Harv 81 Group, specializing in chemical analysis and sensory studies of aroma compounds in wine, cork, and oak. Gus holds a Master of Science degree in Viticulture and Enology from UC Davis, which he earned in 2017, and achieved his MW qualification in 2019. In addition to his research in flavor chemistry and sensory science, Gus is a professional wine educator, offering tutorials to wine enthusiasts around the world.

Resources

- Connect with Gus Zhu

- Unreserved Wine Talk | Episode 217: Flavour versus Taste Plus Uruguay Wines with Nell McShane Wulfhart

- My Books:

- Wine Witch on Fire: Rising from the Ashes of Divorce, Defamation, and Drinking Too Much

- Audiobook:

- Audible/Amazon in the following countries: Canada, US, UK, Australia (includes New Zealand), France (includes Belgium and Switzerland), Germany (includes Austria), Japan, and Brazil.

- Kobo (includes Chapters/Indigo), AudioBooks, Spotify, Google Play, Libro.fm, and other retailers here.

- Wine Witch on Fire Free Companion Guide for Book Clubs

- Audiobook:

- Unquenchable: A Tipsy Quest for the World’s Best Bargain Wines

- Red, White, and Drunk All Over: A Wine-Soaked Journey from Grape to Glass

- Wine Witch on Fire: Rising from the Ashes of Divorce, Defamation, and Drinking Too Much

- My new class, The 5 Wine & Food Pairing Mistakes That Can Ruin Your Dinner And How To Fix Them Forever

Tag Me on Social

Tag me on social media if you enjoyed the episode:

- @nataliemaclean and @natdecants on Facebook

- @nataliemaclean on Twitter

- @nataliemacleanwine on Instagram

- @nataliemaclean on LinkedIn

- Email Me at [email protected]

Thirsty for more?

- Sign up for my free online wine video class where I’ll walk you through The 5 Wine & Food Pairing Mistakes That Can Ruin Your Dinner (and how to fix them forever!)

- You’ll find my books here, including Unquenchable: A Tipsy Quest for the World’s Best Bargain Wines and Red, White and Drunk All Over: A Wine-Soaked Journey from Grape to Glass.

- The new audio edition of Red, White and Drunk All Over: A Wine-Soaked Journey from Grape to Glass is now available on Amazon.ca, Amazon.com and other country-specific Amazon sites; iTunes.ca, iTunes.com and other country-specific iTunes sites; Audible.ca and Audible.com.

Transcript

Natalie MacLean 00:00:00 Can you learn to appreciate aromas such as spice, petrol and even gamey or foxy notes and wine? And would you want to? Should you? How can you better understand the taste of umami in what you eat and drink? And how does culture and lifestyle influence your perception of the aromas and taste of wine? In today’s episode, you’ll hear the stories and tips that answer those questions in our chat with Master of Wine Gus Jue, author of the new book Behind the Glass The Chemical and Sensorial Terroir of Wine Tasting. By the end of our conversation, you’ll also discover why super tasters might be at a disadvantage in the modern world. Oh, why you should pay attention to more smells and tastes in your everyday life. Why we should expand our understanding of terroir. How it felt to become the first Chinese master of wine. Which aspects of Gus’s multicultural education helped him to pass his exam on the first try, which is absolutely incredible given the 10% pass rate. The difference between chemical terroir and sensorial terroir, and why the concept of the tongue map is all sorts of wrong.

Natalie MacLean 00:01:17 And what we do need to know about how our taste buds work. Okay, let’s dive in. Do you have a thirst to learn about wine? Do you love stories about wonderfully obsessive people, hauntingly beautiful places, and amusingly awkward social situations? Well, that’s the blend here on the Unreserved Wine Talk podcast. I’m your host, Natalie MacLean, and each week I share with you unfiltered conversations with celebrities in the wine world, as well as confessions from my own tipsy journey as I write my third book on this subject. I’m so glad you’re here. Now pass me that bottle, please, and let’s get started. Welcome to episode 307. Now, before we dive into the show, I wanted to mention that I was a guest recently on the Full Comment podcast hosted by Brian Lilly, a political columnist for the Toronto Sun newspaper. We were chatting about two counter movements in the market this month Sober October and come over October, like Dry January and Dry July. Sober October encourages participants to abstain from alcohol, tobacco and non-prescription drugs during October.

Natalie MacLean 00:02:45 We discussed why this movement is gaining popularity, especially with generation Z. Possible explanations include the boomerang effect that the new generation always tries to do the opposite of their parents on. Case in point. As a Gen Xer, my Gen Z son doesn’t drink at all, even though, or perhaps because I didn’t make wine forbidden when he was young. And that’s not to say he was swigging Pinot with me at the dinner table each night. Rather, I gave him a taste of a full bodied, very dry red wine. I think it was Cabernet or Shiraz when he was just three years old, and he spat it out with some decidedly non tasting descriptors. True confession I deliberately did not give him a sweet wine so that he didn’t acquire a taste for liquid candy. However, now in his 20s, he has remained a teetotaller even though we’re still close. The only thing we sort of don’t agree on. As a Gen Xer, I was never drawn to the harder spirits or beer of my Boomer parents.

Natalie MacLean 00:03:49 That may be due in part because I’m one of those darn super sensitive super tasters. They were all just tasting too bitter. And I do mean the beer and the spirits, not my relatives. Other possible reasons for the rising trend of sober months include the increasing popularity of non-alcoholic fermented drinks like kombucha, which is a fizzy, fermented non-alcoholic drink typically made with either green or black tea, kefir, fermented milk, or water with kefir grains that has more than 60 probiotics. I’ve been meaning to try that, and alcohol free drinks with adaptogens that have herbs, roots, and other plants like mushrooms that are believed to reduce stress. Of course, there are also far more choices in low and no alcohol wines, beers and spirits that are incredibly well made. Nothing like those sorry ass cooking wines of your sober October may also tie in to the clean lifestyle trend. Much as I don’t like the misleading advertising behind some of it. This includes clean eating, clean beauty, and other clean products that purport not to have any toxic or unnecessary chemicals in them.

Natalie MacLean 00:05:04 And I think finally, when we look at the decline of wine sales among Gen Z, that’s not related to sober October and other dry months, there’s also now more choice for legal recreational drugs, including cannabis, in different formats psilocybin or magic mushrooms, and the favorite of the tech and movie moguls, ketamine, which is a dissociative anesthetic with hallucinogenic effects, as well as, of course, a dizzying array of illegal drugs now in the market. So we have this new counter movement called Come Over October, created by the US wine writer Karen McNeil. This year, its mission, and I’m quoting, is to encourage people to invite family and friends over to come together during the month of October to share some wine and friendship. As she says, we believe that through the simple act of sharing wine, we share other things that matter. Generosity, caring and a belief that being together is an essential part of human happiness. And I say Amen to that. Wine is more than alcohol. It’s community. It’s culture, it’s conversation.

Natalie MacLean 00:06:12 And it’s been around for 8000 years. So it’s deeply woven into the history of humanity. We have an epidemic of loneliness right now, especially post-pandemic. Wine in moderation can be a part of getting us to reconnect with friends and family. It’s also part of a healthy lifestyle. Yes, let me repeat healthy lifestyle. The week after next, I’ll be taking a deep dive into the health benefits of wine as well as the risks with Tony Edwards, author of the new book, The Good News About Wine. We’ll also explore why a number of the recent scary headlines about wine are both misleading and based on junk science. Okay, back to today’s topic. That was quite a rabbit hole we just ran down. Two of you are going to win a copy of Gus’s terrific new book, Behind the Glass The Chemical and Sensorial Terroir of Wine Tasting. All you have to do is email me and let me know that you like to win. I’ll choose two people randomly from those who contact me. In other book news, if you’re reading the paperback or e-book of wine, which on fire, rising from the ashes of divorce, defamation, and drinking too much, or if you’re listening to the audiobook version, I’d love to hear from you at Natalie at Natalie MacLean dot com.

Natalie MacLean 00:07:34 I’ll put a link in the show notes to all retailers worldwide at Natalie MacLean dot com. Forward slash 307. Okay, on with the show. Gus Chiu is the first Chinese national to become a master of wine, and he works as a research and development scientist at Harvey 81 Group in California, specializing in chemical analysis and sensory studies of the aroma compounds in wine, cork and oak. Gus holds a master of science degree in Viticulture and Enology from UC Davis. He graduated from that in 2017 and then achieved a master of wine qualification in 2019. He’s been busy in addition to his research in flavor chemistry and sensory science. Gus is a professional wine educator offering tutorials to wine enthusiasts around the world. He joins us now from his home in Napa Valley. Gus, we’re so glad to have you here with us. Welcome. Thank you.

Gus Zhu 00:08:36 Natalie. It’s great pleasure talking to you.

Natalie MacLean 00:08:39 Great. Your book is so, so fascinating. Congratulations on publishing it just before we dive in there. What was the exact moment you realized you wanted to make wine your career?

Gus Zhu 00:08:50 Well, kind of a long story.

Gus Zhu 00:08:52 I would try to make it short in my childhood. I grew up in China. We don’t have a wine culture necessarily, but we do have some other beverages, especially the infamous 50% alcohol by volume baijiu, the white liquor as a national drinking in China. And I’ve been immersed in these kind of alcoholic beverage smells since my childhood because all the adults at the dinner table, or as some like formal dining settings, they drink those kind of alcohols and those kind of smells actually really fascinates me, probably because my dad smokes and I’m like, okay, sometimes I find it interesting and sometimes I find it a bit not that pleasing. So I was just thinking about those kind of smells a lot since childhood, and then I got a chance to study horticulture as my undergrad degree in China Agricultural University. And in that university, one of the professors, Professor Ma, she hosted this wonderful wine appreciation class, and that got me hooked into wine. And a bit before graduation, I got the chance to be interned at a wine consulting company with two other masters of wines, while back then they weren’t masters of wines, but now they are.

Gus Zhu 00:10:12 So I interned there and I worked there for five years.

Natalie MacLean 00:10:16 Oh wow, what a great introduction to the world of wine, especially through scent, which of course is your fascination and the subject of this book. So take us to the best moment of your career, the Master of Wine. I know it takes thousands of dollars and hours and hours and hours of years of study, but how did you feel when you finally got there and earned this really prestigious designation, especially being the first Chinese national to earn it.

Gus Zhu 00:10:41 Yeah.

Gus Zhu 00:10:41 Of course I felt great. Excellent. Lots of wines and food to celebrate with. but to be honest, I passed the exam on the first attempt, which kind of shocked myself.

Natalie MacLean 00:10:54 Yeah, because the pass rate is only 10% or something really low, isn’t it?

Gus Zhu 00:10:58 Yeah, but in retrospect, I felt really lucky because I had different education backgrounds. So I was a Chinese student in China. We have the very famous college entry exam that basically determine the fate of most people in China, whether you go to a better college and whether you can get better salaries in the future.

Gus Zhu 00:11:20 Right? So we work really hard on it. So we practice a lot for that college entry exam when we hit around 18 years old. And then I got the chance to work with again the two wonderful masters of wines. They are from British education background. so I also learned from them. I also know about Chinese wine market, what’s happening in China. And then I moved to the states doing academic studies at UC Davis. And also I see what’s happening in the United States. So I guess all these worldwide educational experience really helped me. So I feel very grateful and I feel lucky.

Natalie MacLean 00:11:59 Well, well. Okay. Yeah. The heart of your work, the luckier you get, right? Because it’s a tribute to your skills, your intelligence, but also how hard you you must have worked for that. Well done. So tell us in a nutshell what this book is about. Behind the glass. For those of you who are listening to our conversation, we’ll put the link to the book in the show notes, of course.

Natalie MacLean 00:12:20 And the cover. Terrific. So just tell us in a nutshell what this book is about and what makes it different from other books about wine science.

Gus Zhu 00:12:29 So I didn’t intend to write a book from the very beginning, because I just want to put some information together to answer people’s questions, because back in China and even in the States, I’ve been doing some consulting and wine education and lots of people started to ask me questions or they discuss among them saying, okay, why exactly we smell or taste this and that in a glass of wine. And there are quite a lot of questions that can be answered from a cultural or commercial perspective. But in terms of scientific understandings and those kind of answers to those questions is still a bit tricky in terms of, first of all, science is a bit to most people. If people were like, oh, I want to be geeky, but it could be a bit complicated, what if I didn’t learn chemistry? What if I didn’t learn this and that? The second reason is that in the scientific world, there are still quite a few questions that are not answered, Especially in terms of wine tasting.

Gus Zhu 00:13:35 In the book, I actually address some of the aspects that we still need further research on. So I want to put these kind of information down. Maybe I was even thinking about a website or a blog or even vlog, although I don’t know how to make it a nice videos like you can and all these kind of formats. But then I started to talk to my sensory professor, who literally brought me into the sensory science world, and I talked to some other people and I’m like, okay, maybe I can just write information down and try to organize them into a book. And it took me roughly five years. And honestly, the first two years is less about writing. I just write all the information down, which is kind of easy to me because I reference research papers and then use my own words to interpret. But the difficult part is that how do I structure the book? So I thought for about two years until I came up with a structure that I think is okay. So I hope the readers can give me feedback as saying if this kind of structure is easy to understand or not.

Natalie MacLean 00:14:49 Absolutely. And what is the structure of the book? How would you summarize that in a nutshell?

Gus Zhu 00:14:54 It’s very straightforward. It’s just like the title of the book is The Chemical Terroir and the Sensorial Terroir. So it’s basically covers two parts. One is the chemistry part, the other is the sensory part.

Natalie MacLean 00:15:08 Okay, I haven’t heard anybody use those terms. I’m not sure if you came up with them. I mean, in the wine world we hear the word terroir. Often it usually refers just generalizing here soil, climate, geography. There’s other factors. But you have, as you say, chemical terroir versus sensorial terroir. What are they and how are they different.

Gus Zhu 00:15:29 Yeah. Yes. So of course I came up with these terms. And also it’s during my 2 to 3 years of thinking, because the title wasn’t set until probably after two years of writing and thinking. But one day I think is somewhere in Napa. I went to some tastings and people start to talk about terroir again, and then I suddenly came to me that, wow, nowadays, of course, is not about the soils anymore, right? The terroir term originated from the soil meaning from the French world.

Gus Zhu 00:16:02 And I’m like, okay, terroir actually encompasses so many different aspects nowadays. So I personally would just try to explain, hey, anything that can influence the taste of a glass of wine, those factors can be terroirs. So in the introduction part of my book, I use probably two paragraphs, two short paragraphs to explain why the terroir term is so broad nowadays. So I would want to talk about this chemistry and the sensory part of wine tasting. And to make a better, more charming term, I came up with the term chemical and sensorial terroir.

Natalie MacLean 00:16:46 That’s great, expanding our view of terroir. And I’m hearing now terroir is being used in all sorts of things, from olive oil to honey that the bees make to all kinds of stuff. And I’m even hearing words like air where like what’s in the environment that’s, you know, eucalyptus trees and their little oils falling on the grapes and so on. So there’s a lot going on. Mawa, I think, is in the ocean. Anyway, that’s great that you’ve expanding our definition of this.

Natalie MacLean 00:17:10 What’s the most surprising thing you learned while researching or writing the book?

Gus Zhu 00:17:15 I think the surprising things were not those things that we know. As I mentioned, the surprising things were the things that we do not know yet. So I know quite a bit of the wine chemistry, sensory aspects. when I was studying at UC Davis. Also, when I work on my Master of Wine research paper is a sensory research paper. So I was quite confident saying, okay, properly for the basics. I understand quite a lot of them. But then I started to research things. I’m like, oh my God, there are still so many things we don’t understand yet. So that’s the kind of bit surprising. And that is why I spent quite a lot of time again, trying to structure the book in a way that explains the things we know, but also help people to understand that it is actually the things we don’t know that is fascinating and interesting, and we have hope for the future, but also with some foundational way of thinking and understanding.

Gus Zhu 00:18:19 You can actually have a good sense of what the future direction will be, such as we will understand more about our tongue, especially the sense of taste, and also for the sense of smell is the least understood part. And we know that in the future we will reveal more truth about the sense of smell.

Natalie MacLean 00:18:41 That’s great. You do have a very scientific approach and mind. I can tell here. It’s very systematic, very organized. What’s the most interesting thing that someone has said about your book so far?

Gus Zhu 00:18:52 So it’s only been released in UK at the moment, but some of the UK people already said, oh, it’s actually easy to understand, which is a huge relief for me because I really want to write in a way that even people without chemistry or those kind of scientific background can understand, even if they haven’t taste wise yet. I use six pairs of wines at the end of the book. Try to let people practice, even if they haven’t tried those kinds of wines, they could find those even just a sniff.

Gus Zhu 00:19:29 They can find the difference and understand what I talk about in the book. But the feedback I got so far makes me feel like, wow, there are two sort of hidden messages I always say to people that I want to deliver from the book that people started to get and make me really happy. One the message was, number one is that wine chemistry is actually interesting, and fun is not that intimidating. Message number two is that I think it’s more interesting, more fascinating, and more fun to understand your own sensory system.

Natalie MacLean 00:20:06 Yeah, I would agree completely. So you’ve got to appeal to self-interest. And also that, hey, it may be chemistry, but there’s wine involved as well. So it’s a nice combination. Now you’ve written about the misconception about the tongue map. We used to think we had sensors only at the tip of our tongue for sweetness, because that’s what we developed first as babies and so on. And then bitter was always at the back and so on. So why is that wrong? And is it just true that we have sensors for all of the major five tastes, and there’s others that might be in the offing to be developed? Is that true? We have sensors everywhere in our mouths for all of the tastes.

Gus Zhu 00:20:44 Yeah. So I’ll do conclusion first because it’s quite straightforward. Because of the advancement of genetic studies, we now understand that we have tastebuds everywhere in our town. And each taste buds is responsible for all the tastes. So it’s not that, oh, you have a taste for one type of taste in front of the tongue. It’s about one taste buds taste everything and taste buds, they are everywhere. Okay, so that’s a conclusion. So that should be very straightforward.

Natalie MacLean 00:21:19 And are the taste buds also on the like, on the inside of your cheeks and your gums? And like the other parts of the so-called soft palate?

Gus Zhu 00:21:27 Yes. And because of anatomy and genetic studies, people even find out that on the soft palate you still have taste buds. You can still taste all the taste. There are some very tragic incidents where a patient lost most part of his tongue, but he can still taste. Yeah. So again, it’s kind of fascinating to me and why we got it wrong. Why the tongue map got it wrong? Well, it is because in the past, I would say even nowadays, scientific studies, when we look at them, we have to reference different research papers in proper ways.

Gus Zhu 00:22:11 It got wrong when a Harvard psychologist reference a PhD research paper back in the 1940s. 50s in a very wrong way, so that people inherited that kind of town map without even referencing to the true data. And what’s missing in the data, especially when they see the town map. So I think the conclusion is that nowadays is much better in terms of when we do studies and when we publish papers, it has to be peer reviewed. And also nowadays, may I reference one thing that’s written in the book is that we actually almost confirmed that we have a sixth taste. So the five basic tastes are sweet, sour, umami, bitter, salty. Right. And for those five basic tastes, people think, okay, that should be it. But there could be more. So again, with genetic studies, with some other studies, people find out that we should have the sixth taste called fatty taste. So when we can taste the fatty acids, which gives the taste of fat, but it’s not yet fully confirmed.

Gus Zhu 00:23:29 And why is that? It is because scientists are more cautious now. They do not want to make the same mistakes again. So scientists want to prove again and again and again again from different scientific fields. They want to put all the research paper together to 1,000%, verify the fact before they send to media, and the media can finally publish an article saying, okay, we now understand we have a sixth taste. So I think it’s just a matter of time. I would expect in the next five years we will confirm that sixth taste.

Natalie MacLean 00:24:06 How exciting. And you know, I always was trying to get my head around the fifth taste that came to the fore umami, which you suggest or told us. I understand it just very basically being deliciousness or savoriness. How is that different from fat, which I also associate with savory and delicious and round and voluptuous, those kinds of tastes.

Gus Zhu 00:24:28 That’s a great point. That’s an interesting point. Okay. So let me try to explain. So first of all, the taste of umami savory.

Gus Zhu 00:24:38 I have to say as Asian people we are a bit more proud because it’s very easy for us to understand why. Because in Asian countries we have longer history of fermented food products and also in Asian countries in certain period of time and even today, for certain protein based dishes, we do not season those things too much or cook them so much, so that when we taste Certain proteins, such as some seafood or such as even some broth. We do not ask too much salt into it, depending on where you came from. So those kind of protein, amino acids, those kind of pure taste of those kind of things are one mommy. But we often got confused because they are combining with fat, with salt, with all of these things around us. So if you think about if you barbecue mushroom, right, in Western culture, you barbecue mushroom and you just do not season it, and when you barbecue mushroom, there could be some like a juice and broth release in the little dent in the mushroom and you just drink the juice that is the savory, yummy umami taste.

Gus Zhu 00:25:59 And the wonder is a Japanese professor who isolated some glutamates that actually tastes very special. not special, but it’s not mixed up with all these other tastes. It’s more pure that he started to promote the term umami, which actually came from the Japanese term umami, meaning delicious. But actually the kanji of that Japanese term came from the Chinese character savory or umami. And the Chinese character, as I wrote in my book, actually consists of two parts. One part is fish, the other part is lamb. So long time ago. In Asian culture, we understand the pure taste of meat and proteins. Without seasoning, they are closer to the way so-called the Marmite taste.

Natalie MacLean 00:26:50 Wow. That’s fascinating. My goodness. Okay, so let’s dig down into your book. You have various areas as you mentioned. So aromas you discuss sort of a lot of people find vegetal and herbal aromas off putting in wine. How can we learn to appreciate them. Should we? Is it an acquired taste? Just like, you know, when we’re younger, we don’t like bitter tastes of vegetables or whatever.

Natalie MacLean 00:27:13 And then as we get older, we grow to like them. But what is your take on vegetal and herbal aromas?

Gus Zhu 00:27:20 So those are related to sense of smell, which again is a least understood part, but at least for certain smells throughout evolution, it makes sense that we reject certain smell. For example, if a plant or fruit or food smells vegetal, it’s a sign of under ripeness, not that ripe, right? So that in theory, we naturally do not like something that smells pretty green. However, many, many, many of those kinds of smells in very low concentrations or at the right amount of concentration, okay, they actually serve as Important functions in our body or from the outside, as communicating tools in between animals and plants in between us and the nature. So we also learned to like certain smells because they have a function. So I think in a lot of cases is more about that right amount of things. For example, in certain wines people say, oh, there are certain smell.

Gus Zhu 00:28:32 What the wine industry called the reductive smell. They found a stinky indeed. Certain of those kind of smell smells like rotten eggs. They are stinky. But sometimes people say, oh, I also smell some flinty smells from some white Burgundy wines. And what he said is fascinating. I’m like, hey, those are also radioactive smells. Now you don’t find them stinky. It is because the right correct compound with the right amount of concentration actually stimulates people. so it all depends. It’s such a fascinating world and we only know probably 0.1% of those kind of smells.

Natalie MacLean 00:29:11 Lots of work for you to do in the future there, Gus. But yeah, you’re right. Even in perfumes, like, I’ve read a couple of books about the making of different perfumes because it’s so closely parallels wine. And just sometimes they’ll put the weirdest things in there, almost. You would think they’d be putrid, but there’s just like that base note or something like an orchestra. You need that sort of the different notes combining to make that beautiful sound together.

Natalie MacLean 00:29:37 And if it’s all sweet and, you know, beautiful flutes, then it’s not that interesting, right?

Gus Zhu 00:29:42 Exactly. And some of the agents they put in certain perfumes we don’t even want to talk about in this video because I’ve heard.

Natalie MacLean 00:29:49 Of ambergris from whales. That’s like excreted ambergris and it’s like expensive.

Gus Zhu 00:29:56 Well.

Gus Zhu 00:29:57 And you know what? Ambergris, it has certain smells. That is classified in my book. Now, a bit technical is a big group of aromas called the tabloids. They have tons of noise like turpentine. Yeah. So people in the wine world, they always say Turpin. So Turpin is a type of noise. So let’s just say Turpin. Which one? People, knows the most. So Turpin actually, people say, oh, I smell Turpin. No, Turpin has probably 20 thousands of different compounds. So for certain Turpin you can find in ambergris and for certain Turpin you can find in wine and for certain things you can also find it in different plants or different animals. And some of them are extremely attractive to people in terms of smell.

Gus Zhu 00:30:48 Some smells could be very strange or revolting, such as the petrol smell in Riesling is also a type of Turpin noise. So it’s a type of Turpin. It’s just so many of them.

Natalie MacLean 00:30:59 Well, I bizarrely love petrol, but then again, it reminds me of summers by the lake with the outboard motor and going to gas stations and loving the smell of gasoline. I don’t know, maybe I was getting high as a kid in the back seat, but it is bizarre, you know?

Gus Zhu 00:31:14 Not really, because I also explained in my book, there’s always connections. You know what? Nowadays even some biofuels were synthesized by turbines. So there’s correlations.

Natalie MacLean 00:31:28 Yeah. And it’s all closely tied to memory as well. So it’s powerful. What turbines would we like. Aside from my bizarre liking of petrol. But what do people generally say they like in the classification of terpene smells.

Gus Zhu 00:31:43 I will say most hairpins people like because if you think about most of the flowers, they have turbines. And also in Asian countries, maybe all over the world now people burn some wood like incense, right? Incense has lots of trapping smell.

Gus Zhu 00:31:59 So there are certain things, such as I mentioned aroma therapies in the book, that they actually use a lot of terpene smell to help people become calm and relaxed and making them feel better. But I also mentioned that this is something we probably going to talk a lot later is that do not just say this chirping smell will make you feel good, because certain people, they could be anomic to it. They cannot smell certain aromas and also to certain people. Like the same terpene smells great, but at the same time to some other people because of how they brought up and because of their genetics, they found it disgusting. So it really depends on people’s variability on smelling things as well.

Natalie MacLean 00:32:46 Absolutely. You mentioned as nausea as no smoke. Is that like a blind spot for one particular odor.

Gus Zhu 00:32:53 So anosmia specific anosmia. Everybody has certain kinds of specific anosmia. It doesn’t mean you are better or worse. It just means that the genes related to sense of smell is just so broad and so complex. So there has to be some, I would say, bugs or glitches for your sense of smell.

Gus Zhu 00:33:17 Right? And usually it is because evolution wise we started to lose certain smells because they are not that important to us anymore. The site is more important to people, but the sense of smell is not that important in terms of survival. I kind of disagree with that kind of explanation.

Gus Zhu 00:33:39 In the liquor.

Natalie MacLean 00:33:39 Store. Well, then again, you can’t smell the wines in the house. Yeah, but I get it. Like we’re very visual as a culture.

Gus Zhu 00:33:45 Yeah. So of course, to us wine professionals, we always think sense of smell is very important. But evolution wise, Yes. Certain sense of smell, we just lose it. And if you think about a trillion different coatings for our genetics, for the smell, right, there must be for each person some of the genetic codings will go muted or they will go through some changes. So we really start to smell things differently from each other.

Natalie MacLean 00:34:17 Yeah. Now everyone’s different. But does there tend to be 1 or 2 smells that are high on that hit list of a lot of people can’t pick this up the smoke as much as noses or whatever.

Gus Zhu 00:34:28 Yeah, it’s a very interesting. Yeah.

Gus Zhu 00:34:30 twist.

Gus Zhu 00:34:30 Term. Yeah.

Gus Zhu 00:34:32 So sorry. This is a very, not very, but all the technical terms and jumping from the book. But I will say it’s hard to predict you have to do studies. And that is why in our field, when we do sensory science, we always see differences among people. And for certain types of things, such as the sight, Like you can actually test genetics and find out if you are green, red, colorblind or not. You can just see that. And also for the sense of taste, you can just see people. Some people are super sensitive to certain taste on the tongue and certain people are not. It’s quite obvious, but for the sense of smell, it just so unpredictable. You can find some of the most. We’re probably going to address that term super tasters for the taste. They are very sensitive, but for the nose, for certain smells, whether or not they are sensitive to certain aromas is so unpredictable.

Natalie MacLean 00:35:28 That is interesting. I was tested by Tim Hanai tonight in California and it turns out I am a super taster, but it’s a bit of a misnomer as he likes to point out continually on social media that it doesn’t mean you’re a better taster, but just you’re more sensitive to that bitter compound, right?

Gus Zhu 00:35:48 Yeah. So Tim Hannah is one of the inspirations for my book. He always advocate how we taste differently from each other. And of course, indeed, nowadays we find out that at least for the taste, again, not smell, but for the taste we can see certain people are super sensitive and certain people are not that sensitive. So for those kind of very sensitive people, we say they are super tasters. However, I always say that they are actually in the modern society. They are not that how to say they are a bit of unlucky because.

Gus Zhu 00:36:26 So since there are so.

Gus Zhu 00:36:27 Many, yeah, there are so many things they cannot eat, like spicy food, like even, let’s say now even we have a trend of lower alcoholic beverages, right? But even low alcohol wine or those kind of beverages to those super tasters, they still taste the burn from alcohol.

Gus Zhu 00:36:46 So that’s a bit I feel bad for them.

Natalie MacLean 00:36:49 That’s okay. You don’t have to feel too bad for us so we can get around things by training and practicing, but I still I can’t walk past the olive section in a grocery store. If those olives are out, like on a buffet style, it’s like, it’ll make me sick. That smell though. But anyway, yeah, it’s interesting. Now you you talk about unpleasant aromas. Others like foxy and Gamey, maybe tell us a bit about what those really are. If we can put language to help people understand what those aromas are, maybe how they appear in wine, what your discussion around those aromas is in the book?

Gus Zhu 00:37:22 Yes, those are less about the sensory or chemistry based, I think for those kind of gamey and interesting aromas from the nature. I think people should just eat and drink more and pay more attention to nature. And why is that? Because I have to say, especially I live in different cultures, right. In China we eat lots of weird parts of animals.

Gus Zhu 00:37:46 But if you think about like a European countries in the past, even the more noble people, the emperors, those kind of people, they eat the eyeballs of certain animals or they eat the tongue of certain animals, and they usually contain certain gamey or foxy or interesting tastes. But in North America, especially in United States, I found probably because of, you know, the history people tend to eat meat. That’s very I shouldn’t say bland. But if you think.

Gus Zhu 00:38:17 About, say, I think it is generally okay. Refrigerated like supermarket.

Natalie MacLean 00:38:21 Meats are very bland. Yeah, yeah.

Gus Zhu 00:38:23 But if you do not like those weird taste meat, it’s okay. It’s totally up to you, your lifestyle. But I just want to say those people who like a Chinese will eat all parts of any animals. Probably we actually experience more of those kind of interesting tastes, whether or not we like it is a personal thing, but actually in our culture we do appreciate more of those kind of tastes simply because of the higher diversity of exposure.

Natalie MacLean 00:38:57 Yeah. So gaming, I get kind of like game meats like bison or buffalo or sometime or deer, venison or whatever. It’s kind of like not as well. It’s a bit more exotic, I guess, to.

Gus Zhu 00:39:11 Yeah. Yes.

Natalie MacLean 00:39:12 Exotic to the North American palate. I should recalibrate my, my assumptions here. I get that like that those kind of aromas in food and drink I guess. But what is foxy? Surely we’re not referring to the little fox and wine tasting like the fox, are we?

Gus Zhu 00:39:31 It is when people started to describe those kind of aromas. It tastes kind of related to the foxy smell from a wild fox fur like smell, but I’m pretty sure there are some related aroma compounds, but in most cases it’s just people trying to use a reference point to describe the smell. That is again, why I emphasize on the fact that if you experience more smell and taste, or you pay attention to more smell and taste in your life, the more descriptors you will have. So if you look at most of us right in the wine industry, we really pay attention and explore all sorts of food and beverages, and we pay attention to the smells around us because that is helping us to build up the vocabulary.

Gus Zhu 00:40:26 But on the other hand, one of the struggles for us also to you and to most people probably, is that when we try to communicate our media, there are just so many people from different cultures and some people may just not pay attention to smells at all, which is totally fine. Most people are like that, but it’s just hard to communicate, right? Because we lack reference points. But to, let’s say color to vision to the shape is so easy because people see colors every day. People see this kind of triangle versus round shape every day. So it’s super easy. But for the sense of smell is super difficult simply because we were not brought up by paying attention to different smells.

Natalie MacLean 00:41:11 Absolutely. Like, you know, I could easily tell you that and communicate easily to someone else russet, fuchsia, pink, orange like in there, all in that sort of reddish spectrum, but foxy, feral gamey like then I’m thinking, that’s hard. Yeah. It’s hard.

Gus Zhu 00:41:28 Yeah.

Natalie MacLean 00:41:29 Cool. Well, there you have it.

Natalie MacLean 00:41:37 I hope you enjoyed our chat with Gus, here are my takeaways. Number one. Can you learn to appreciate aromas such as spice, petrol, and even gamey or foxy notes in wine? And would you want to or should you? Well, as Gus explains, we have evolved to reject certain smells for our survival. For example, if a plant or fruit or other food smells vegetal, it’s usually a sign of under ripeness so it either doesn’t taste good or isn’t nutritious enough for consumption. And in some cases it could mean that it’s poisonous. So it makes sense then, that we may not like vegetal aromas in wine. Number two, how can you better understand the taste of umami in what you eat and drink? In Asian countries, Gus says they have a longer history with fermented food and drink. They also don’t overseas and or overcook protein dishes so that the taste of yummy remains. Yummy comes from the amino acids in protein. But we often get it confused because we combine our proteins with fat, salt and other things.

Natalie MacLean 00:42:39 If you barbecue a mushroom and don’t season it, the juice or broth released into the little dent into the mushroom is a savory, yummy umami taste. And number three, how do culture and lifestyle influence your perception of aromas and taste of wine? Gus believes that we should pay more attention to what we eat and drink. In China. They eat lots of different parts of animals, but in North America, especially in the US, he finds that people tend to eat meat that’s very bland. He believes that those who eat like the Chinese experience a more diverse range of flavors and develop a greater appreciation of them. Similarly, we develop a greater vocabulary to express what we’re eating and drinking when we think about it. In the show notes, you’ll find the full transcript of my conversation with Gus, links to his website and book the video versions of these conversations on Facebook and YouTube live and where you can order my book online now no matter where you live. If you missed episode 217, go back and take a listen.

Natalie MacLean 00:43:43 I chat about the difference between flavor versus taste with New York Times author Neil McShane Wolfhard. I’ll share a short clip with you now to whet your appetite.

Nell McShane Wulfhart 00:43:56 What we hear can change the flavor of what we’re eating. There was a great experiment by Charles Spence. He called it think the sonic chip. He gave a bunch of people in a lab, some Pringles out of the can, and he put headphones on them. And for some of the people eating the Pringles, he turned up the volume of their own crunching. And those people perceived those chips as being fresher than the ones who just heard it at the regular volume. In general, smell is definitely the most powerful one, especially when it comes to things like wine. And it’s that flavor. It’s a smell plus the taste, plus the other senses that creates flavor. Flavors really created more in your mind than it is on your tongue.

Natalie MacLean 00:44:39 You won’t want to miss next week when we continue our chat with Gus. If you liked this episode or learned even one thing from it, please email me or tell one friend about the podcast this week, especially someone you know who’d be interested in learning more about how to improve their ability to taste wine and food and identify those aromas and flavors like umami.

Natalie MacLean 00:45:00 It’s easy to find my podcast. Just tell them to search for Natalie MacLean Wine on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, their favorite podcast app, or they can listen to the show on my website at Natalie MacLean. Com forward slash podcast. Email me if you have a SIP tip question, or if you’ve read my book or are listening to it at Natalie at Natalie MacLean. Com in the show notes, you’ll also find a link to take the free online wine and food pairing class with me, called the five Wine and Food Pairing Mistakes That Can ruin your dinner and how to fix them forever at Natalie MacLean dot com forward slash class. And that’s all in the show notes at Natalie MacLean dot com forward slash 307. Thank you for taking the time to join me here. I hope something great is in your glass this week. Perhaps a wine that makes you pay attention to it and you pair it with a new mamey rich dish. You don’t want to miss one juicy episode of this podcast, especially the secret full bodied bonus episodes that I don’t announce on social media.

Natalie MacLean 00:46:09 So subscribe for free now at Natalie MacLean. Com forward slash subscribe. Meet me here next week. Cheers!