They were all young women whose families owned the great champagne houses at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

They were all young women whose families owned the great champagne houses at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

When they lost their husbands to war or illness, they did not do what was expected: step aside or sell the business. Nor did they marry again (though they were still in their twenties and thirties), handing over the reins to a new husband.

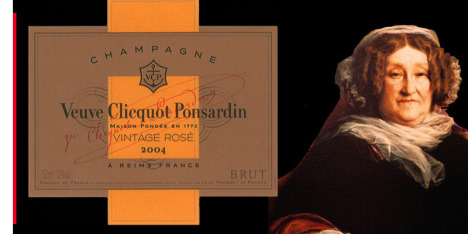

Instead, these celebrated veuves, or widows, took control of their châteaux to produce some of the most prestigious wines in the world – wines that still bear their names: Veuve Clicquot, Pommery, Laurent-Perrier, Roederer and Bollinger.

Instead, these celebrated veuves, or widows, took control of their châteaux to produce some of the most prestigious wines in the world – wines that still bear their names: Veuve Clicquot, Pommery, Laurent-Perrier, Roederer and Bollinger.

In an era when few women were in business at all, these women headed what were, at the time, some of France’s largest companies.

Using bold, unconventional strategies such as direct marketing campaigns and exporting to unproven markets, each of them more than doubled production during their tenure.

Why did these women step up, rather than aside? It certainly wasn’t because of material needs: most came from wealthy families, and selling the business would have provided a comfortable income for the rest of their lives.

Nor did they take on the business as a surrogate for frustrated maternal affection: all but  one had young children when their husbands died.

one had young children when their husbands died.

But what they had in common was a desire to honour both the memory of their husbands and their families, who had made wine for generations.

And so they carried on that tradition to deal with their grief and to pass the family legacy on to their own children.

Their bred-in-the-bone work ethic would not allow them to just sit and knit doilies for the rest of their lives. Instead, they seized the opportunity to fulfill an aspect of themselves that otherwise would have been neglected.

Probably the most famous woman of this group was Barbe-Nicole Clicquot Ponsardin, of Veuve Clicquot. Her husband died of a malignant fever in 1805, when Madame Clicquot was 27, leaving her with the business and an eight-year-old daughter.

But she was not one to wring her hands: only weeks after the funereal, she arranged for the shipment of 25,000 bottles to Russia — an extraordinary feat, given the uncertainty of trade during the Napoleonic wars.

But she was not one to wring her hands: only weeks after the funereal, she arranged for the shipment of 25,000 bottles to Russia — an extraordinary feat, given the uncertainty of trade during the Napoleonic wars.

Her shipment got through, and years later, her champagne was so popular in Russia that Pushkin, Gogol and Chekhov all wrote about it.

Later, in 1814, when the Russians invaded her home town of Reims and raided her cellars, she said, “Let them drink. They’ll pay for it later.”  Veuve Clicquot Winery

Veuve Clicquot Winery

Read Part 2 of Champagne Widows