Part 2: Champagne Widows

Part 2: Champagne Widows

By the 1930s, French winemakers faced even greater challenges: a country about to go to war, a worldwide Depression that made running any business difficult, and U.S. Prohibition, which made selling luxury champagne to the lucrative American market almost impossible.

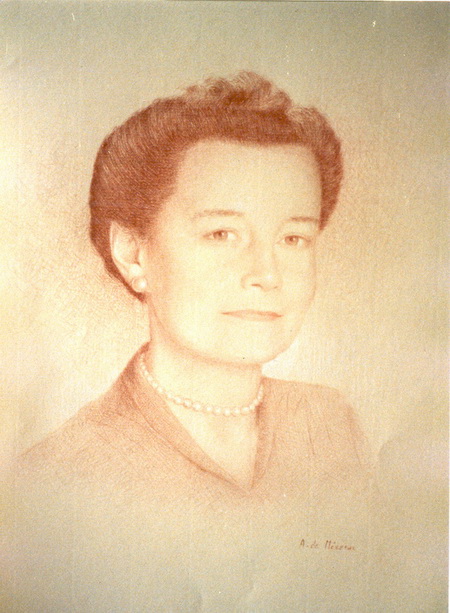

This was the forbidding business environment that Camille Olry-Roederer stepped into when she took over the champagne house Louis Roederer after losing her second husband in 1932 (her first husband had died in World War I).

Sales were 264,000 bottles that year, compared to 2.3 million bottles in 1876.

But like the other women of Champagne she persevered, hiring professional sales and export managers, and travelling abroad to open new markets.

Jamin Grand Prix Amérique 1962

Jamin Grand Prix Amérique 1962

New York Herald Tribune 31 July 1960

New York Herald Tribune 31 July 1960

She was head of the House of Roederer for forty-three years, until 1975, when her grandson, Jean-Claude Rouzaud, took on the role. Today, the house also makes highly regarded sparkling wine in California.

2016-® COPYRIGHT J.-M. CURIEN -® ERIC_ BRIFFARD

2016-® COPYRIGHT J.-M. CURIEN -® ERIC_ BRIFFARD

2016-® COPYRIGHT -® MENTION OBLIGATOIRE PHOTO J.-M. CURIEN -® MARC_HAEBERLIN

2016-® COPYRIGHT -® MENTION OBLIGATOIRE PHOTO J.-M. CURIEN -® MARC_HAEBERLIN

Langoustines Feuillantines au Sésame by J.-M. CURIEN ©

Langoustines Feuillantines au Sésame by J.-M. CURIEN ©

Today, the merits of Cristal, Roederer’s flagship Champagne have been put to lyrics in the rap songs of Jay-Z, P-Diddy and others, often with creative pairings, such as Cheetos.

Today, the merits of Cristal, Roederer’s flagship Champagne have been put to lyrics in the rap songs of Jay-Z, P-Diddy and others, often with creative pairings, such as Cheetos.

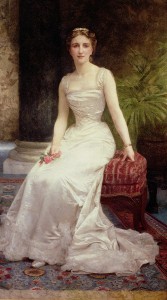

Elizabeth Law de Lauriston-Boubers

Elizabeth Law de Lauriston-Boubers

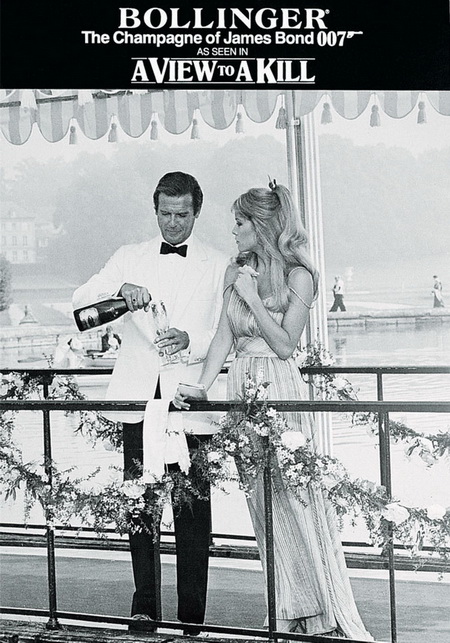

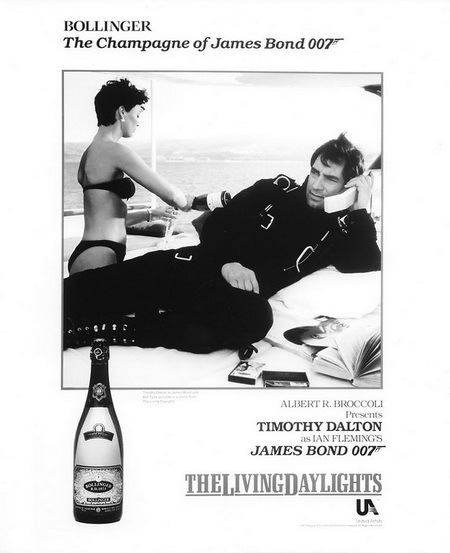

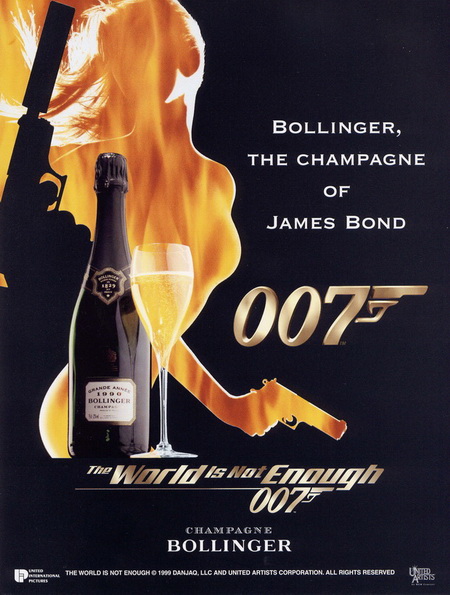

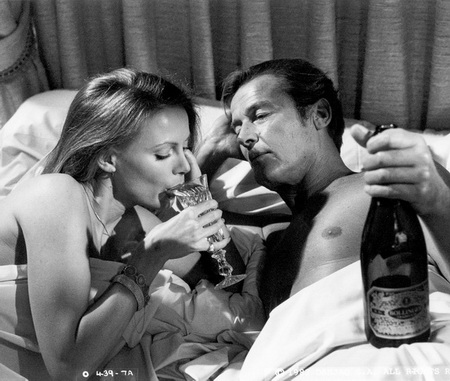

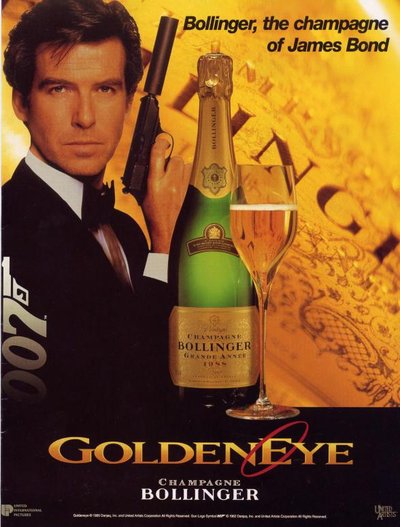

Of all these pioneering women, possibly the most colourful was Elizabeth Law de Lauriston-Boubers, known as Madame Jacques, or Lily, who ran the champagne house Bollinger from 1941 to [email protected]

Her first taste of champagne wasn’t until her engagement party in 1923, before she married Jacques Bollinger, the third generation of the family to make the wine.

When the Nazis invaded France in 1940, they took 178,000 bottles of champagne, but the Bollingers agreed to keep producing the wine in order to free their employees from prison camps, and to protect their home and winery.

Despite Allied bombing to oust the Germans, a depleted labour pool, and shortages of electricity, water and gas, Madame Bollinger was usually in the vineyards by 6 a.m., often riding her bicycle up and down the vineyard rows.

At night, with her château commandeered by the Germans, she slept in the cellars. U.S. liberation came not a moment too soon: on August 22, 1944, General Patton’s Third Army arrived just in time to stop the retreating German army from dynamiting the Bollinger cellars.

After the war, she continued her groundbreaking work. In 1969, to mark her 70th birthday, she introduced Vieilles Vignes Françaises – the first champagne made from only pinot noir grapes.

She also created Bollinger Rosé. Over the thirty years that she ran the winery, she doubled its sales to more than a million bottles. In 1976, the French government awarded her the Ordre National du Merit.

Madame Bollinger embodied the love of life possessed of all of these grandes dames de champagne:

“I drink champagne when I am happy, and when I am sad,” she said. “Sometimes I drink it when I’m alone. When I have company I consider it obligatory. I trifle with it if I’m not hungry, and drink it when I am. Otherwise I never touch it – unless I am thirsty.”