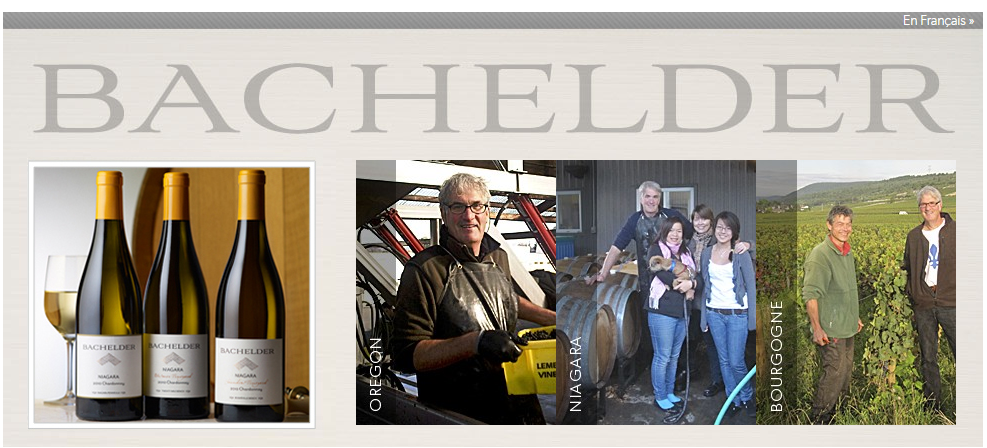

Last night, we had two spectacular, on-fire conversations with Canadian rock-star winemaker Thomas Bachelder.

Click the arrow above to watch part one before the internet gods cut us off ;) Part two is below.

It was a wide-ranging conversation sprinkled with limestone and lyrical story-telling.

You’ll find his wines under his own Bachelder label as well as Domaine Quelyus.

You’ll find previous and upcoming Live Video Wine Tastings here.

Want to get the heads up on Facebook when we go live next Sunday?

Take 3 seconds right now and click on these 2 grey buttons under the wine bottle image:

Sip with you soon ;)

This five-part report on organic wines includes:

Part 1: What is organic wine?

Part 2: The headache over wine and sulfites.

Part 3: Is organic wine healthier for you?

Part 4: Differences between organic, biodynamic and sustainable farming?

Part 5: How to buy the best organic wines?

By Natalie MacLean

Earth Hour has passed, and Earth Day is almost upon us. Naturally, you might think about pouring yourself a glass of organic wine on April 22. But what is organic wine and how is it different from “inorganic wine”?

Back in the 1970s, the concept of “organic wine” conjured up images of pony-tailed vintners in tie-dyed T-shirts, producing wines more for ideology than taste. Thankfully, those days are just a watery memory now.

Today, organic wines are no longer just for health nuts and tree-huggers. Wine lovers drink them for their quality. They’ve gone mainstream and represent one of the fastest-growing categories in the liquor store.

Getting into the mainstream required settling some key issues, and that story reveals as much about contemporary life as it does about organic wines. Until the 1950s, most grapes grown for wine (like most crops of all kinds then) were “organic”: that is, they were grown without using synthetic pesticides and fertilizers.

This often meant that crops were at the mercy of diseases and pests and farmers had no choice but to wait until nature re-calibrated itself after the blight died out with its food source, the crop.

Then along came the so-called “green revolution” and the chemicals perceived as the modern and progressive way to farm. They seemed to offer problem-free fields without destroying the crops.

For two decades or so, these intensive and expensive interventions ruled agriculture in North America and around the world.

The backlash started with the back-to-the-land movement of the 1970s. Consumers worried about the domination of big business, about harm to the environment and the long-term effects of chemicals used to produce food and drink.

Scientists now believe that all such substances accumulate in our bodies; and since they’ve only been used for a few decades, we don’t yet know the long-term effects.

These factors, together with the yearning for self-sufficiency of the hippie culture, strengthened the public desire for natural food products.

Modern food concerns since then—genetically modified foods, mercury poisoning, mad cow disease, fast food, and obesity—have all contributed to the momentum.

What is organic wine?

Many foods are described as “organic” nowadays, but what does it actually mean applied to wine? Making wine is a two-step process: first you grow the grapes and then you make the wine.

That means there’s a difference between wine from “organically grown grapes” and “organic wine.” Grapes that are organically grown must have no synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides or soil fumigants used on them.

Do organic wines use chemicals or not?

The concept that organic grapes are grown without chemicals is misleading. All wine grapes use some form of chemicals in farming, the difference is that organics use chemicals derived from naturally occurring materials.

For example, most organic wine grape growers use sulfur to control powdery mildew and so do  conventional growers. The only difference is that the formulations of sulfur used by organic farmers are approved by the U.S. National Organic Standards Board whereas the sulfur used by conventional growers can be any sulfur.

conventional growers. The only difference is that the formulations of sulfur used by organic farmers are approved by the U.S. National Organic Standards Board whereas the sulfur used by conventional growers can be any sulfur.

In both cases, these materials are pesticides. It’s true that all synthetic pesticides and fertilizers are “synthesized,” which requires energy. However, organically approved sulfur dust is mined, which also consumes a lot of energy, whereas most synthetic sulfur dust is a by-product of petroleum distillation.

There’s still debate over whether organic grapes are allowed to be irrigated with “gray water” (partially treated waste water). Purists also nix the use of genetically modified vines and growth hormones.

To qualify for the organic designation, the farm or vineyard must be free of synthetic chemicals for a certain period as determined by governmental agencies, such as the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

This varies by country, but three years is the most common length of time for the soil to be declared free of most chemical residue. “Organic wine” takes the no-chemical use a step further.

It means that not only were the grapes grown organically, but the wine itself was then made with none of the 500 available additives and agents.

Who defines what’s organic?

This is a confusing subject because different winemaking regions use different definitions and several organizations provide a number of different certifications.

For example, the California Certified Organic Farmers organization inspects and certifies member growers according to its own standards, which are more stringent than those in the California Organic Food Act of 1979.

Many producers are advocating a single set of international standards, which would help consumers to understand and trust the organic designation.

What do organic vintners use instead of synthetic chemicals?

In their quest to enrich the soil and keep pests at bay, many vintners inter-plant the vine rows with other crops, such as rye grass, chicory, fescue, oats, mustard, lupins, and red clover. These cover crops control weeds and encourage bugs to feed on them rather than on the vines.

They can also be plowed back into the soil to replenish its nitrogen. Some organic winemakers also add compost made from pomace, the solid material left over from pressing the grapes.

Some vintners allow chickens the run of their vineyards, since they both eat bugs and scratch the soil, naturally tilling it. Others build nesting boxes and perches to encourage hawks and owls to roost and hunt rodents and other pests in the vineyard.

This can be surprisingly effective. Doug Price, viticulturist at the California winery Clos de Bois, once laid out a tarp under one of the 30 owl boxes he built around the vineyard. Over the course of one summer, it collected more than 500 gopher skulls.

Featherstone Vineyards in Niagara uses “lamb-mowers” to reduce their environmental hoof print: the spring lambs eat the low-hanging leaf canopy of the vines as well as the graases growing between vineyard rows.

What about those ladybugs?

Another tactic is encouraging the “good bugs” to eat the “bad bugs.” For example, the Malivoire winery released more than 100,000 ladybugs into its Niagara vineyards during the 2001 harvest to feast on leafhoppers—pesky insects with a taste for grape leaves.

Malivoire’s label bears a drawing of a ladybug in tribute to this helpful insect, and one of its wines is named Ladybug Rosé. The advantage is that ladybugs are selective about what they eat, whereas insecticides destroy every bug in its path, and leave a vineyard more vulnerable to pest attacks the next year.

The ladybugs are selective about what they eat, whereas insecticides destroy every bug in its path, and leave a vineyard more vulnerable to pest attacks the next year.

But wait, didn’t ladybugs taint Niagara wines a few years ago? After wines were barreled or bottled for the 2001 harvest, many winemakers noticed an odd smell of rancid peanut butter. A number of wineries, including Malivoire, pulled their affected wines from store shelves that year.

Eventually, they traced the problem to an Asian species of ladybug, quite different from the indigenous five-spotted ladybugs. Farmers in the southern U.S. had introduced the bug to feed on the aphids that were plaguing their pecan trees and soyabeans.

The problem began when these ladybugs migrated north, following the aphids, and became a seasonal pest in wine country. Swarms of these beetles amass whenever a cold snap is followed by an “Indian summer.” They hibernate in the grapevines, which offer both food and warmth as winter approaches.

When the affected grapes were picked and crushed, these stowaway ladybugs emitted a foul fluid called pyrazine that smelled like rancid peanut butter. The smell also has a dampening effect on the wine’s natural fruit aromas similar to mild cork taint.

Wine tolerance for this type of beetle is low: more than four beetles per four-tonne bin can ruin the entire harvest. Martin, though, is philosophical about the problem: “It’s just Mother Nature doing her thing and we’re the ones who have to adapt.”

The good news is that early-ripening grapes, such as sauvignon blanc, provided the first warning about the problem. Martin and other vintners largely addressed the issue before it affected pinot noir and other later-ripening grapes.

Vintners have also learned how to deal with the pests: spraying the vines with certain chemicals, harvesting at night when the beetles aren’t active, shaking them out by hand when picking the grapes and sorting the grapes before crushing them.

The sorting table at Malivoire starts with a heat blower to blow off intruders, then the grapes travel along a vibrating belt to shake them off with workers picking them out, and then the grapes go past a final heat blower.

This five-part report on organic wines includes:

Part 1: What is organic wine?

Part 2: The headache over wine and sulfites.

Part 3: Is organic wine healthier for you?

Part 4: Differences between organic, biodynamic and sustainable farming?

Part 5: How to buy the best organic wines?