Continued from Part 2 of Catena Wine

Continued from Part 2 of Catena Wine

That “little project” lasted fifteen years and involved planting 145 Malbec “clones”: the same grape, but from different parent vines, to see which clones would do best in different sites.

(“Wine caters to obsessive personalities: it makes you worse,” Nicolás observes with a sigh.)

He knew that until the late 1800s, when phylloxera destroyed most European vineyards, Malbec had been one of the most planted grapes in Bordeaux whereas today, it’s less than ten percent of vineyards there.

Malbec still thrives in the warm region of southwest France called Cahors, which makes a tannic, deeply colored, palate-whacking “black wine.”

This may be why the name Malbec is believed to be derived from the French mal bouche—”bad mouth,” referring to this rustic style.

Alamos Wine Reviews and Ratings

Alamos Wine Reviews and Ratings

Thankfully, Argentine Malbec is a much friendlier, cuddlier creature than the inky monsters of Cahors.

(I recall drinking Cahors for the first time and thinking that I could use it to re-stain the front deck.)

Ever the scientist, Nicolás narrowed down all those clones to the five best, a process he says that married his bookish and business interests.

“As a theoretical economist, I’m trained to develop a hypothesis and then to use a methodical approach to prove or disprove it,” he explains, taking off his glasses and rubbing his eyes.

He was aided in this quest by a friend, Bordeaux winemaker Jacques Lurton, who also has wineries in both Chile and Argentina.

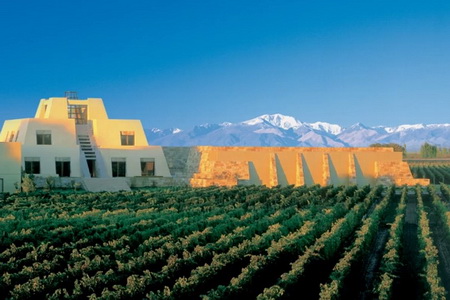

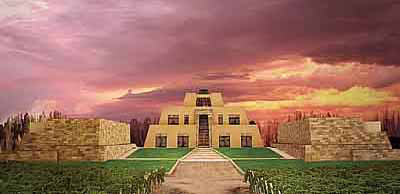

Lurton convinced Nicolás to plant at higher altitudes, which further improved the grape quality. (“Jacques has a genius for climate.”)

In gratitude, Nicolás had a thousand pounds of prime Argentina grass-fed beef delivered to Lurton in Bordeaux.

Like many artists, Nicolás is fascinated with light: its luminosity, its diffusion, its interplay among the vine leaves:

“It’s all about funneling that extraordinary intensity of sunlight here into the wine.”

His scientific mind is also engaged with light, studying its effect on the health benefits of red wine. Intense sunlight doesn’t mean hotter temperatures, just more intense rays.

The intense ultraviolet light at higher elevations speeds photosynthesis, making it more efficient, so the plants are healthier.

It also causes the grape skins to thicken in an attempt to protect themselves from the increased radiation.

This accelerates the development of natural compounds, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and anthocyanins, that give wine its color, tannin, and flavour.

These compounds or phenolics in grapes grown at over fifteen hundred feet are three times higher than in grapes grown at sea level.

The phenolics help to inhibit the development of endothelin-1, the nasty enzyme that blocks arteries and contributes to heart disease.

The phenolics help to inhibit the development of endothelin-1, the nasty enzyme that blocks arteries and contributes to heart disease.

Since only red grape skins are fermented with the grape juice, these benefits are mostly in red wines.

(I love it when I can rationalize my alcoholic intake with medicinal benefits. And at my rate of consumption, I should live forever—or at least be well-preserved [completely pickled] by the time I make my exit.)

The result is wine of extraordinary elegance, with a rare combination when young: solid structure and silky texture.

Argentine wine isn’t just bottled sunshine; it’s the liquid expression of solar energy.

When I drink Malbec, I feel voluptuous and expansive—that’s probably why I’m also often wearing my buffet pants with the elasticized waistline.

I like to indulge my thirst and my hunger to just this side of plump. I’m tall so I can pack away the pounds without many people noticing.

Of course, confessing things like this in print defeats that notion and will only make me even more self-conscious on the next book tour—if there is a book tour. Perhaps I could do talking head videocasts instead, or maybe I’ll just have to wear the black buffet pants for two weeks.

Read Part 4 of Argentine Wine …