It’s just been announced that Oscar winner Matthew McConaughey will star in movie adaptation of the wine book The Billionaire’s Vinegar by Ben Wallace.

Will Smith bought the rights and will be directing this production along with Todd Black, James Lassiter, Jason Blumenthal, and Steve Tisch.

No indication yet of which role McConaughey will play or of the release date for the film. I can’t wait to see it!

Here’s my review of the book in the Globe & Mail …

Reviewed by Natalie MacLean

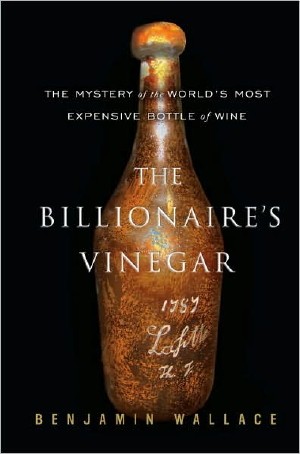

The Billionaire’s Vinegar: The Mystery of the World’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine

By Benjamin Wallace

Crown Publishers, 304 pages, $27.95

An old bottle of wine is rare, but a ripping good mystery about one is rarer still. The tale of The Billionaire’s Vinegar begins on December 5, 1985, in the tony West Room of Christie’s London auction house.

Lot 337, a hand-blown, dark-brown bottle of 1787 Château Lafite, is held aloft for all the bidders to admire. The reason: not only is this the oldest bottle of wine ever to come up for auction, but the glass is also etched with the letters “Th. J.”—supposedly the initials of Thomas Jefferson, America’s founding father and the purported former owner of this prize bottle.

Among the bidders are two men particularly determined to take home this piece of liquid history: Marvin Shaken, publisher of Wine Spectator magazine, and Kip Forbes, son of publishing billionaire Malcolm Forbes.

Among the bidders are two men particularly determined to take home this piece of liquid history: Marvin Shaken, publisher of Wine Spectator magazine, and Kip Forbes, son of publishing billionaire Malcolm Forbes.

After a white-knuckled volley, lasting just one minute and 39 seconds, between the two paddle-wielding contestants, auctioneer Michael Broadbent brings down the gavel. Forbes triumphs with a bid of $156,450, the highest amount ever paid for a single bottle.

But whose victory is it?

That’s what author Benjamin Wallace wants us to discover in his first book. The former executive editor of Philadelphia magazine, Wallace has a great story to tell—a mystery worthy of Grisham or Clancy—and he builds the tension clue by clue.

That particular bottle was part of a cache supposedly found in 1985 by a German pop-music-promoter-turned-wine-buyer named Hardy Rodenstock.

He claimed that he discovered them in a walled-up Paris cellar, though he was secretive about the original owner and other details. The sale made headlines around the world, driving skyward the prices of other fine wines as the public was fascinated by the numbers: a glass of wine costing thousands of dollars, sips for hundreds.

Of all the compelling portraits in this book, the most intriguing is of the elusive Rodenstock. As Wallace describes him, his “stolid moon of a face [was] barely interrupted by small, opaque eyes and the faintest suggestion of a mouth. What you remembered about him, were not the stippled-in details, but the big-brush outlines … when he shook your hand, he would click his heels.”

After the Jefferson sale, Rodenstock continued to miraculously discover many more rare wines in hidden cellars from Russia to Venezuela. Rodenstock and his friends host lavish competitive tastings that often turned into gluttonous marathons.

One such event featured two hundred vintages of Lafite-Rothschild and another was a week-long tasting of the coveted dessert wine Château d’Yquem.

Possibly the most over-the-top of these patrician pleasures was a reenactment of a 1867 dinner attended by Czar Alexander II of Russia, his son and heir Alexander III and the future first emperor of Germany, Wilhelm I. The eighty guests were served only wines that would have been consumed at the original feast. Fittingly, Rodenstock called this event The Three Emperors Dinner—bringing to mind the fable of the Emperor’s New Clothes.

At least one man began to suspect that buyers of Rodenstock’s wines were dressed in nothing but their illusions: American billionaire, Bill Koch. He decides to authenticate four more of those Jefferson bottles he’d bought in 1988 for $500,000.

His suspicions are aroused by the lack of historical documentation. Thomas Jefferson was an obsessive record-keeper: he kept copies of all his 16,000-odd letters and of even his most minor expenses, such as the payments for oats for his horse when he was in Paris. But none of his many ledgers makes any references to the purchase of these expensive bottles.

A litigious fellow, Koch hired a former FBI agent to investigate Rodenstock, spending more than a million dollars of his own money. After exhaustive testing, he concluded that the bottles were in fact fakes, and in July 2006, he sued Rodenstock for fraud. That’s where Wallace’s telling of the tale ends, as his book went to press. Since then, though, a U.S. judge ruled that the New York court lacked jurisdiction over Rodenstock, so Koch is pursuing his quarry in European courts.

Wallace’s narrative leads us into a world of heiresses, celebrities, rogues, bankers, tomb raiders, dilettantes, villains, Arab potentates, American millionaires, and as the tale darkens, forensic scientists, glass and  handwriting experts, Jefferson scholars, FBI agents and federal court judges.

handwriting experts, Jefferson scholars, FBI agents and federal court judges.

The tale of Rodenstock allows us to indulge our fascination with con artists, with their galling hustle to get what they want and their inventive intelligence to elude capture. No wonder actor-producer Will Smith is making a movie based on the book.

Wallace is brilliant at sketching characters with delicious details. There’s Christie’s auctioneer Michael Broadbent, for instance, who at 58 was still “pedalling to work each day on his Dutch ladies bicycle with a basket, legs gunning furiously, a trilby hat perched on his head.” He shows his “boyish sense of marvel at the longevity of wine” and describes it variously as having aromas of crystallized violets, clean bandages, dunked gingernuts and schoolgirl uniforms.

Other vivid personalities are wine collectors, such as Marvin Overton III, “a Texas neurosurgeon who sometimes wore a bolo tie with a fur coat” and the shadowy Lloyd Flatt, “an eyepatch-wearing Tennessean” believed to be an international arms dealer.

As Wallace follows the story, he parallels America’s hard-won connoisseurship over the last 20 years with Jefferson’s own journey from touring the vineyards of France to attempting to make his own wine back in Virginia, observing that his 1787 trip to France made him the greatest wine connoisseur writing in any language. In America, wine moved from a little-understood but pleasurable beverage to drinkable art and investment vehicle.

Wallace also explores the subjectivity of wine and the suggestibility of human nature. Even experienced drinkers are strongly influenced by the pronouncements of experts, such as the American critic Robert Parker. He also observes the perceived relation of price to quality. Since the book was published, a telling experiment underscores his point: in a blind taste test of two glasses of the same wine, participants preferred the one that they were told was more expensive.

For those who can’t stomach another wine guide, The Billionaire’s Vinegar makes learning about wine more palatable. The book touches on the history of wine auctions and how they work, on how wine is priced and how it gains rarity, on the importance of vintages and crop yields, on bottle sizes, wine tasting, glassware, wine and food matching, wine criticism, and collecting and cellaring wine.

Not all wine books are destined to languish on the coffee table, sampled only occasionally to confirm a fact: some are meant to be gulped down from cover to cover.

One of his most poetically instructive passages is his description of how wine ages and transforms into a more life-altering experience than say orange juice. When oxygen interacts with young wine, all the components soften and knit together, especially the astringent tannins, which “drift down into a carpet of sediment, taking with them the saturated, inky pigments.” What’s left is a “mellowed, unfathomably subtle flavor.” He points out the paradox of wine: time makes it great and time destroys it. But the very unpredictability of aging wine makes it thrilling.

Wallace also delves deeper into what makes wine authentic. He notes that Dutch merchants dosed claret with brandy to help it survive long sea journeys to distant markets. Famous châteaux have historically “reconditioned” old bottles to prevent them from oxidizing: topping them up with wine of the same or younger vintage.

The spectrum of wines considered authentic is almost as varied as the shades of fakery: labelling inferior vintages with superior ones, blending vintages, topping up vinegarized wine bought cheaply at auction, replacing the wine with another wine or even with another liquid, such as colour-dyed water.

Until recently, with the advent of fraud-prevention technologies, wine was one of the easiest products to fake. The reasons are partly physical: One bottle looks much like another, labels are easy to reproduce with desktop publishing and the product can’t be tested without consuming it. Partly they’re psychological: if a pricy bottle tasted like vinegar (hence Wallace’s title), often the rich-but-unsophisticated buyer isn’t confident enough to know that this isn’t how the wine should taste. Partly they’re time-related: Buyers often don’t open their bottles until years later, by which time the fraudster is long gone.

In the Rodenstock case, all of these factors came together to create the perfect storm. Châteaux owners didn’t want to admit that their bottles could be faked, critics didn’t want to confess to being fooled, auction houses didn’t want the $70 million market to collapse and buyers didn’t want to know that their cellars were full of fakes.

In chronicling these events, Wallace brings a reporter’s discipline to both the depth of his research and to his even-handed treatment of his findings. This is both the book’s strength and its flaw. He might have done more than just confirm court briefs, quote published articles and reference interviews with the key players.

He might, for instance, have included more in-depth personal interviews with these characters. More importantly, he could have given us a much stronger personal opinion of the events and facts. Instead, he is dutifully journalistic to the end.

What The Billionaire’s Vinegar is really about, though, more than wine, is desire: the desire of con artists to get what they can and the desire of the victims to believe what they wish. Desire runs through this book like wine sediment: shifting, murky and tinged with bitterness.